Our bus ride meanders through the Andalusian region known as “Pueblo Blanco,” which signifies nineteen whitewashed villages scattered between Ronda and Cadiz.

This morning, we will visit the home and ranch of famous bullfighter Rafael Tejada. The Reservatauro Ronda is a free-range ranch where Spain’s renowned fighting bulls are raised alongside Andalusian horses and the beefier horses of Picadors. Tejada’s bullring is the only all-native stone ring in Spain and is used for bullfighter training and fighting stock evaluations.

Calves and their nursemaids are separated in vast enclosures from fighting cows, fighting bulls, and oxen that may harm them.

Only females are used for teaching in the bullring. The females and their calves are tested for fighting instincts before they are accepted for breeding and training. Every bull, cow, and calf must consistently prove it’s a badass by nature to remain in the program.

Spain’s fighting bulls are prized for their aggression, energy, strength, and stamina. Raising them free-range maintains their natural mean streaks. Human encounters are limited and never on foot. Oxen may be used to herd them as horses are no match for the brawny bulls. The fighting bull’s first encounter with a toreador, bullring, and boisterous crowd is their debut to die in the bullring.

In contrast to the fighting bulls, Andalusian horses are usually gray, built strong and compact, and renowned for their smarts, sensitivity, and docility. This stud bears the scars of kicks and bites from females who are not always open to his advances.

The bullfighter’s cape is red to camouflage blood stains, as the movement, not the hue, is what enrages the color-blind bull. Capes are made of very heavy nylon and cotton to keep them from flapping in the wind. We were surprised to find they weighed 9-13 pounds.

Modern bullfighting is done on foot, not horseback, and it harkens back to Roman gladiators fighting animals with swords. Picadors ride blindfolded horses and stab the bull’s neck with lances to make the bull less dangerous. The two barbed darts the matador stabs into the shoulders weaken the bull’s neck and shoulder muscles and make it more aggressive. The third act is a choreographed dance with a red cape, demonstrating the matador’s control of the bull before the animal is stabbed through the shoulder blades into the aorta of its heart for a quick and clean death.

If a bull and matador fight extremely well, the crowd may wave white hankies, and the bull may be given a reprieve. It is a rare occurrence, but it happened to Rafael Tejada. He bought the spared bull to begin the bloodline for Reservatauro Ronda and mounted its head when the bovine stud died. The picture of Tejada in the upper left corner depicts his goring in the upper right leg and the bull lifting him off the ground. This is a fatal injury when the aorta is severed. Rafael survived with a 12-inch scar to remind him of his second year in the ring. Rafael’s passion and reverence for the animals and participants in bullfighting are immense. He strives to teach the cultural and historical importance of bullfighting and leaves the criticism to others.

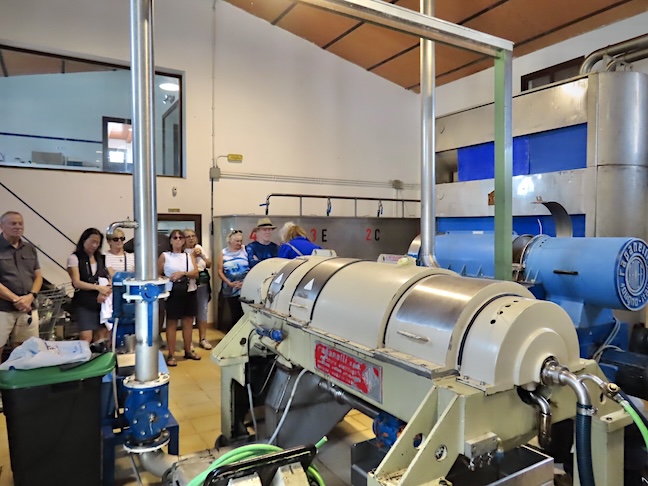

Our next stop is a traditional olive oil mill. The owner grows and accepts local farmers’ olive crops for processing. Olive harvests are offloaded into the seeding machine, cleaned, and the meat is conveyed into his plant.

The seeded olives are ground into a paste and then spun in a centrifuge to separate the oil from the pulp and water. The oil is filtered and stored in stainless steel tanks.

The highest-quality extra virgin Spanish olive oil is cold-pressed to preserve the flavor and maintain more antioxidants and vitamins than virgin olive oil, which endures a degradation process. During our olive oil tasting, we learned about varieties like Picual, Hojiblanca, and Arbequina, as well as oils with fruit and spice flavor infusions. Oils are not as much fun to taste test as wine.

The owner of the olive oil mill hosted our farm-style lunch, featuring different varieties of olive oil and foods that pair well with them. It was delicious.

We checked into the Hotel Casa de las Cuatro Torres in Cádiz, where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean in the Strait of Gibraltar. Cádiz is considered the oldest continuously inhabited city in Western Europe, founded by the Phoenicians 3100 years ago. We walked the rocky coastline to the western end, searching for a place to watch the sunset.

La Caleta is the only beach in the walled section of Cádiz. A literal hole-in-the-wall bar you can’t see from the sidewalk above serves sunset lovers on the beach and specializes in tinto de verano made with red wine and lemon soda on ice. “Tintos” became our refreshing drink of choice.

The sunset was gorgeous! After dark, we wandered through the narrow cobblestone streets that are curvy to slow down high winds that blow in from the ocean. We stumbled into a local pizza place and took a pie and salad back to our hotel to eat on the rooftop. The ancient allure of Cádiz is still present.